Field Notes #2: Narwhal Research

This is part of a series of field notes from Greenland. Read Field Notes #1: Niaqornat or view all related Imaging the Arctic posts.

Narwhals (Monodon monoceros) are shy and elusive Arctic whales that spend the winter in the extreme pack ice environment of eastern Canada and Greenland. Until the 19th century, there was widespread belief that the iconic tusk of male narwhals was from a unicorn! While we know better today that the narwhal is a real animal, they remain relatively mysterious and much is still unknown.

Approximately 80% of the world’s narwhal population (estimated at 90,000 animals) lives in Baffin Bay between West Greenland and Canada. Narwhals winter in dense ice cover and dive extraordinarily deep to feed on Greenland halibut or other species. In Baffin Bay they may reach depths of 4,500 feet, 15-20 times a day, taking over 30 minutes round trip. The record narwhal dive depth obtained by Dr. Kristin Laidre and colleagues is 5,905 feet.

The habitat and behavior of narwhals makes them difficult to study. In order to successfully research narwhals from the pack ice, a number of variables need to line up perfectly. The first requirement is clear safe flying weather for the helicopter to reach the narwhals offshore.

The whales need to be within the 3-hour fuel range of the helicopter (AS-350). Otherwise, barrels of fuel must be slung out with the helicopter (hanging from the bottom) and placed temporarily on the ice so the helicopter can refuel “at sea” during the search for narwhals.

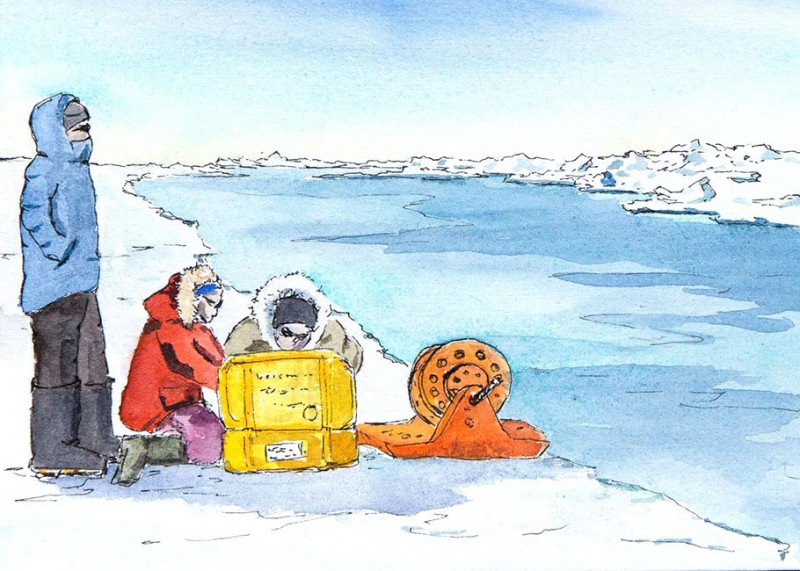

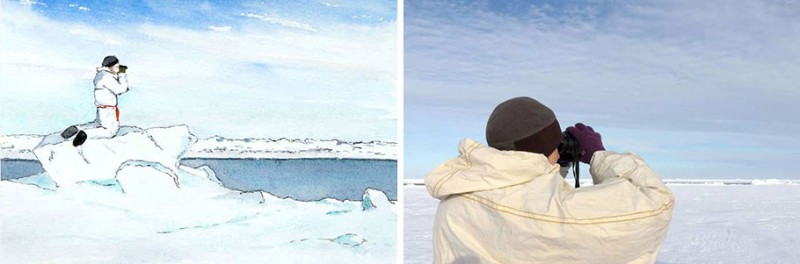

Next, the whales must be spotted in ice leads (cracks in the ice) with surrounding ice that is strong enough to support the weight of the helicopter landing. Then the narwhals need to stick around long enough them to be recorded or tagged!

They are very skittish animals, and often dive after the helicopter arrives, or if they hear people walking over the ice and setting up equipment.

With luck, the narwhals return to the same lead after 20-30 minutes to catch their breath, but a lot of time is spent watching and waiting for them.

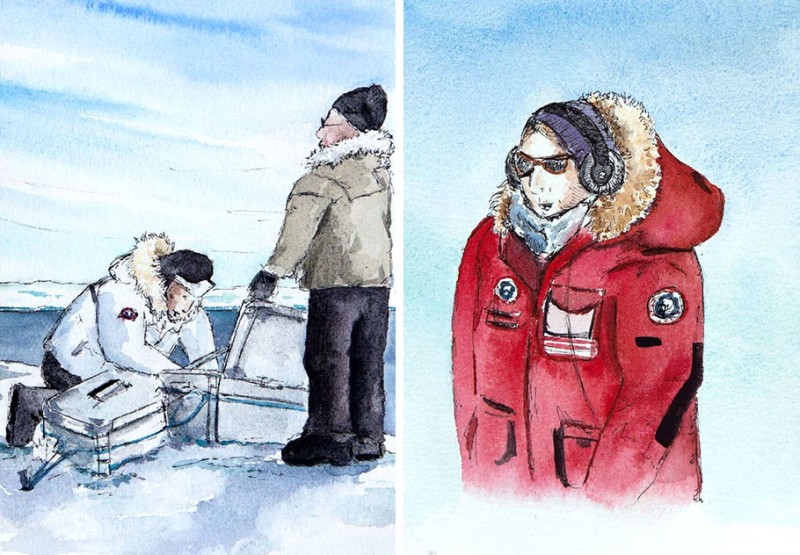

Finally, the scientific equipment needs to work. The pack ice is a harsh environment for electronics (temperatures are -20C plus strong wind) and batteries and computers freeze within minutes if exposed to the air. Kristin describes with a laugh that getting any data from narwhals in winter is 50% luck, 40% preparation, 10% optimism (or insanity)!

Kristin collaborates with two bioacousticians, Jens Koblitz from the German Oceanographic Museum and Dr. Marianne Rasmussen from University of Iceland, Husavik Research Center, who each have systems to record marine mammals.

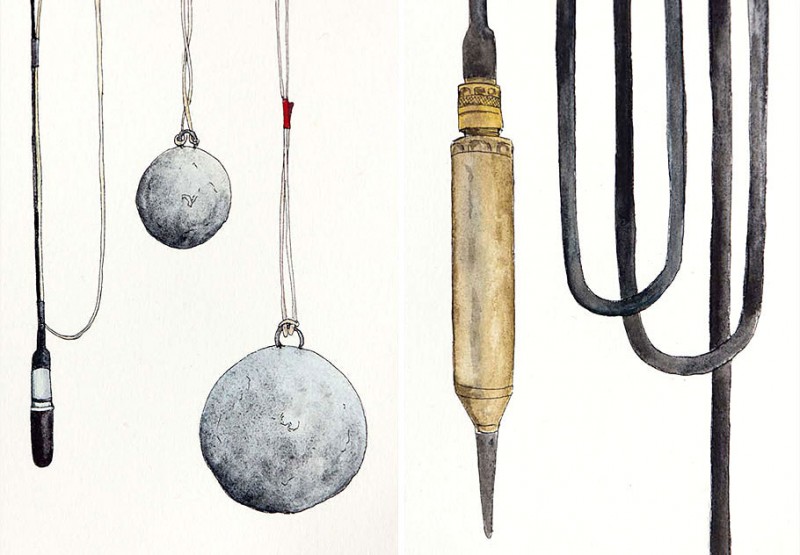

One is a vertical array of 16 hydrophones lowered into the water on a cable down to 60 feet, and another is a very sensitive single hydrophone that goes to 400 feet. The systems record different sound features that illustrate how narwhals find food and communicate.

Kristin also works with Mikkel Villum Jensen to place satellite tags on narwhals from the leads by shooting small transmitters into the blubber with an airgun. They have to dress in white and quietly sneak up on the narwhals to even get a chance to tag them.

The satellite tags send data on how the narwhals move around in the sea ice, how deep they dive, and how long they spend underwater at different depths.

This project will create a baseline understanding about narwhal acoustics and behavior in the Arctic. Climate change is causing sea ice loss and ecosystem shifts and the narwhal’s Arctic habitat is undergoing large changes from human impacts, such as shipping, tourism, and oil exploration. Monitoring narwhals allows us to understand how they are responding to these changes and may help inform future decisions.

This is part of a series of field notes from Greenland, read Field Notes #3: Kullorsuaq or view all related Imaging the Arctic posts.

Leave a Reply