High Latitudes Part 5: Polar Bear Encounters

This entry is part of an ongoing series. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

After learning I’ve spent time in the Arctic, people often ask me, “have you ever seen a polar bear?” For years the answer was no. In 2005, the closest I came to a polar bear was sketching a skull lent to me by the Upernavik Museum in NW Greenland. Arriving on Sand Island in NE Greenland, the only evidence I initially saw of bears was an old jawbone on the beach.

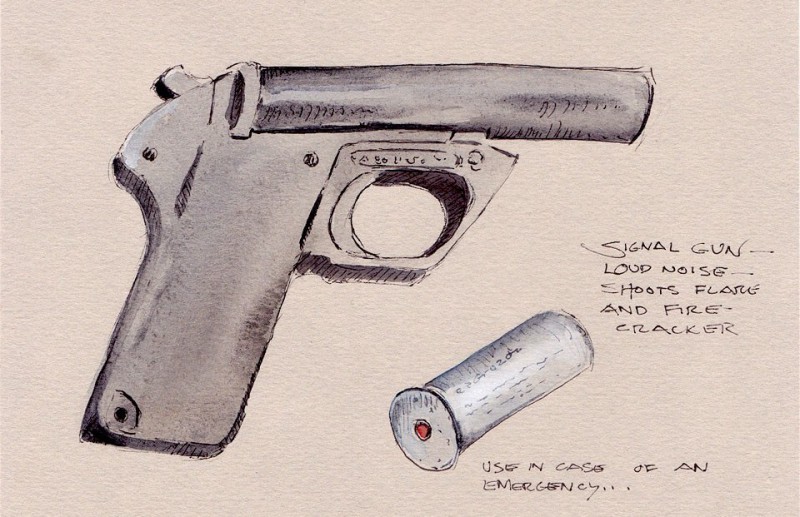

We knew there were polar bears in the region, though. For one, Danish biologist Dr. Erik Born, whose walrus research camp I was visiting, was monitoring satellite signals in the Young Sound area from a female bear he’d collared the year earlier. We took several government mandated safety precautions to protect ourselves in case we were paid a visit. First, we had a number of flares, which could be set off like firecrackers towards an aggressive animal. Next, we had a signal pistol, which could shoot very loud and smokey flares off to the distance. Finally, we carried two rifles.

Scientist Dr. Erik Born warned me to be especially attentive for bears while sketching and to make an effort to look up every minute or so and scan the horizon. In the 1920s, an artist was attacked by a polar bear… I didn’t want to repeat history! On the small island, I’d carry a minimum of the signal pistol and a radio, and the few times I went hiking on the mainland, I’d carry a radio and flares, as well as a rifle. It could be cumbersome with my art materials!

In spite of our vigilance, we were all surprised one afternoon by an approaching polar bear, while we were lying in the sand surveying a group of sunbathing walruses. We were downwind of the animals, and the young bear that began walking up the beach of the small island (~300m x 500m) was downwind, too, and must have caught their scent. It wasn’t until the bear was within 45 feet of us (approaching from our backs) that Erik noticed it. He jumped up, shouted, “bear!”, and grabbed the rifle. Startled, the bear hightailed down the beach and we watched it swim up the fjord.

Seeing the bear was thrilling and I became even more vigilant while out sketching. One day, I looked up from my work and saw a motorboat pulling up on the beach. Curious, I wandered down to say hello to the unexpected visitors. I was shocked when I saw what was onboard: a dead polar bear that had attacked a man just an hour earlier on a nearby island.

My colleagues on Sand Island had previously worked with Greenlandic hunters to sample polar bears for contaminants (heavy metals, etc…) and offered to take biopsies and butcher the bear. Feeling both fascinated and saddened by the incident, I jumped aboard to sketch and learn.

We motored up Young Sound fjord for ten minutes to the Daneborg station and were met by a crowd. After off-loading the bear, the butchering process began and I sketched. After a while I noticed a man nearby with bandages on his wrist looking pale. He was the archeologist who survived the attack. Shyly, I asked him for his story which he generously shared with me. I later sent him my polar bear sketches in return. Hear his account of the attack and see my art below.

As per regulations for when a polar bear is killed in self-defense (they are a protected species), the skin was prepared to send to the Greenlandic government. With respect for the bear, the meat was divided among research teams and cooked for dinner. My culinary highlight was eating strips of meat prepared with a dark chocolate whisky sauce. For another meal, I helped cook polar bear curry that was shared with a group of 40 people. Before eating, we listened to the story of the man who shot the bear, saving his colleague’s life. The whole experience gave me vivid dreams.

One Response to “High Latitudes Part 5: Polar Bear Encounters”

Sandra Andrews-Strasko

Wow. This is so detailed. Thanks for the pictures and the audio. I had been curious to hear more about this attack since you had mentioned it to me. Not so often you get to “talk to” someone who was attacked by a polar bear.