Behind the Data: Every Egg, Every Chick

This is part of a series, read my previous post: Cooper Island: First Impressions

Accompanying scientists in the field, I’ve come to appreciate the amount of effort and resources required to collect data, particularly in remote polar regions. In addition to the usual challenges of fieldwork, George Divoky brings a tenacious drive and dedication to maintaining his study of Cooper Island Black Guillemots in the Arctic for the past 45 consecutive years.

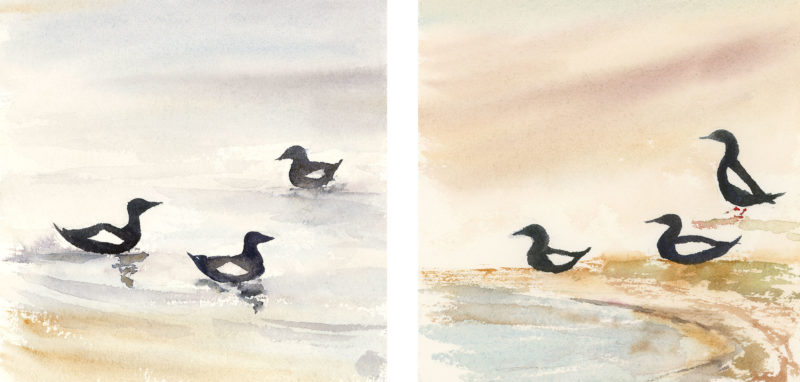

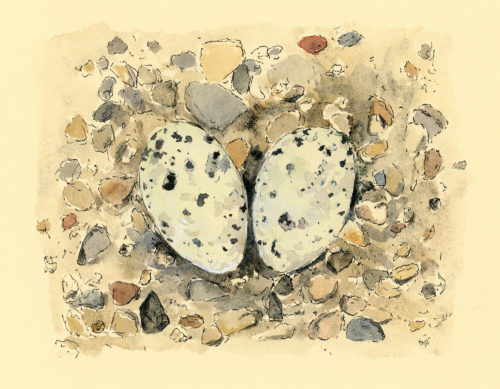

George Divoky first found the Black Guillemot colony of Cooper Island in 1972 when there were only ten pairs. While most sea birds nest in formidable cliff cavities, the Cooper Island guillemots found nesting cavities under old pieces of wood. The planks and boxes were remnants of Navy structures abandoned and destroyed after the Korean War. The accessible nesting sites presented George an opportunity to study the breeding biology of Black Guillemots.

The colony grew to about 200 breeding pairs each summer, with nests from wood debris and later boxes to protect the birds from hungry bears. Each summer, George returned to the arctic to spend three months on the deserted island to observe the colony. By the 1990s, he noticed the birds responding to the decreasing sea ice in the arctic, and began to view his data through the lens of climate change research. The colony was in decline; in 2018, there were only 75 breeding pairs.

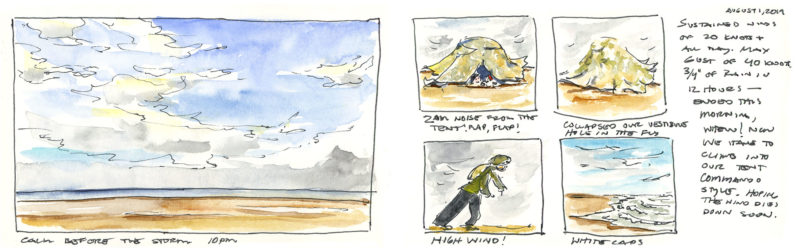

Beyond the daily tasks necessary for surviving on a deserted island in the Arctic for three months, George collects data day in and day out as he monitors the guillemot colony. His work continues despite cold, wet, or windy conditions, as I experienced during our visit.

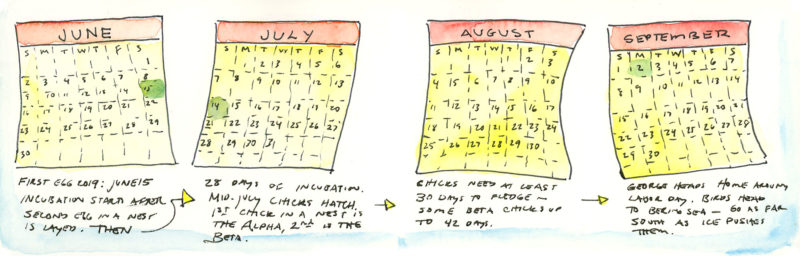

He begins in mid-June when the guillemots return to the island from their winter range in the Chukchi sea. George surveys the colony, recording which birds have returned to their breeding sites. At times it’s like welcoming back old friends as he sees a bird that he banded 20 years ago.

After the bird pairs have formed, the birds incubate their nests for a period of 23-39 days before the chicks hatch. During this time, George focuses on setting up his camp, including his wind generator, tents for guests, a weatherport for food storage, and an electric fence for polar bear safety.

As the eggs start hatching, George becomes extremely busy, weighing each chick in the colony daily to record their growth. These are time-consuming, but critical data points as chick weights reflect the availability of nutritious prey fish that their parents are bringing back.

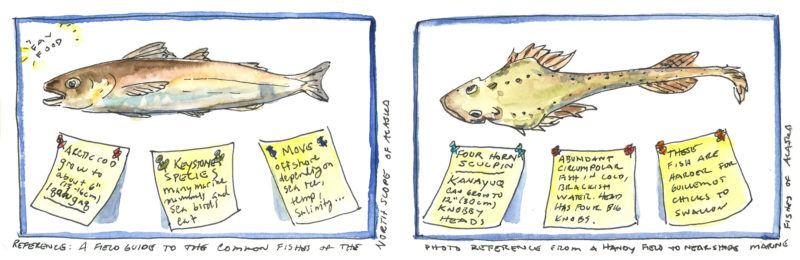

A decrease in available prey is one of the loud climate change signals George has observed. Black Guillemots live at the edge of sea ice, where they forage for their preferred diet of Arctic Cod. The cod are nutrient-rich cold-water fish, adapted to living under the ice in sub-freezing waters. As temperatures in the Arctic Ocean have warmed, the availability of Arctic Cod around Cooper Island has decreased dramatically. Guillemots forage for alternative fish, often the bottom-feeding fourhorn sculpin. The sculpins’ large bony heads are difficult for chicks to swallow and are also not as energy-rich as the cod. George has observed a corresponding decline in chick weights and survival.

Last summer on Cooper Island, the lack of Arctic Cod in the nearshore was apparent. Our arrival on the island coincided with about half of the 130 newly hatched chicks succumbing to starvation. Each day we followed George around visiting nest sites, helping weigh chicks, measure wing growth, and record data. We celebrated each weight gain, knowing it would increase the chick’s chances of survival. Because of the grim start to our visit, the handful of growing birds felt like a victory, and we rooted for them daily. In the end, however, only 25% of the chicks fledged. For a colony that once had over 200 active nest sites, many of which would fledge two chicks, the number of healthy individuals paled in comparison.

In his 45 years on Cooper Island, George has documented over 10,000 eggs laid and weighed chicks more than 80,000 times. Each egg and chick is part of the story of survival and adaptability that the arctic, and our world, is facing with climate change. And on Cooper Island, George Divoky is there to record it.

In my next post, Tools for Research

Read more about George’s Cooper island research:

2 Responses to “Behind the Data: Every Egg, Every Chick”

Isabel Patchett

Dear Maria,

thank you so much for another wonderful blog post, I do so much enjoy receiving your mail and reading all you have to say. And to see the artwork is so wonderful I look forward to sitting down this afternoon to go through it all.

I am looking forward to your “Witnessing Climate Change” exhibition although it is always very sad to see what is happening to our beautiful planet. Thank you for sharing so much with us. Sincerely Isabel

Maria

I so appreciate your support and encouragement, Isabel! Thank you for sharing my journeys. All my best, Maria