Tools For Research: Monitoring the Colony

This is part of a series, read my previous post: Behind the Data: Every Egg, Every Chick

I love learning about the tools that different professions use to observe and study our world. Joining biologist George Divoky on Cooper Island in 2019, I sketched and experienced how he monitors the Black Guillemot colony, collecting data daily once the chicks have hatched.

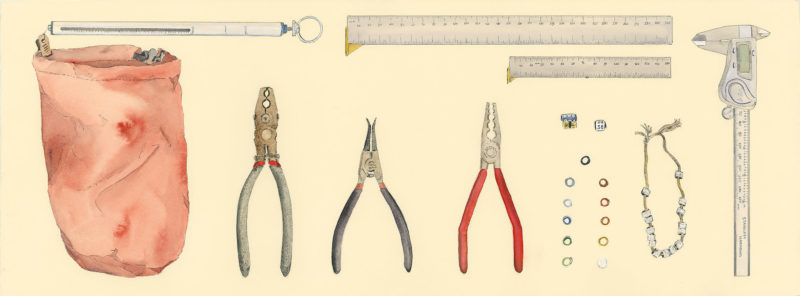

George uses a spring scale to weigh chicks, and measures their wingspans to determine their growth rates. Their health relates to the availability of prey their parents are able to forage for. Each bird is banded with a unique three-colored combination of anklets to mark and identify individuals. This allows us to study bird behavior from a distance and determine pair formation, breeding success, and lifespan.

For example, WOGy (white-orange-gray) fledged from Cooper Island in 1975, returned in 1980 and was banded. He continued to return and breed on Cooper Island each summer until 2001. Each bird also receives a metal band from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Friends of Cooper Island maintains a database of over 3,000 birds banded on Cooper Island.

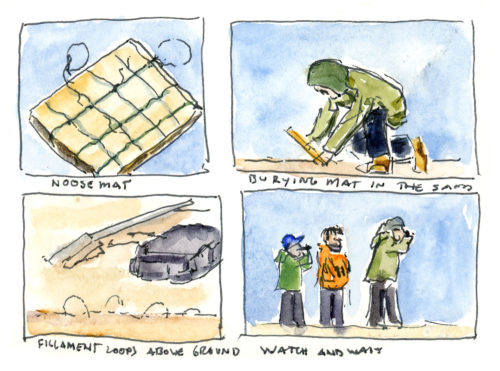

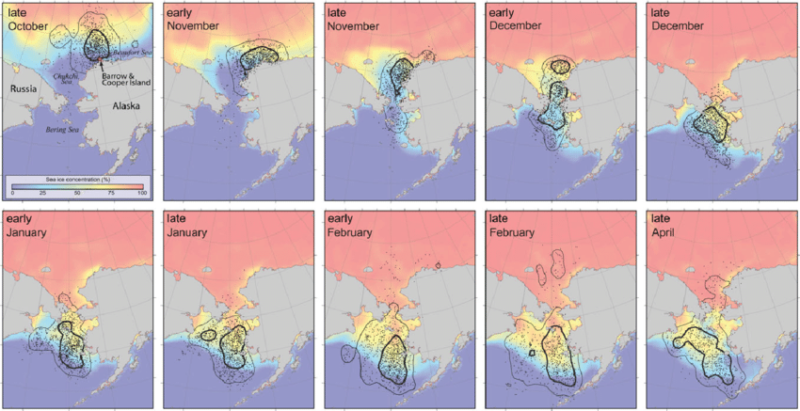

To learn the winter range of this non-migratory seabird, George uses geolocators. These are small, light-sensitive units that can be attached to birds’ legs to help us determine their location. The tricky part is capturing the adult bird to attach the locator, and recapturing it the following year to download the data! George has a system to patiently (and gently) noose the legs of birds.

The downloaded data provides valuable information about the winter range of this non-migratory seabird!

Another useful tool for monitoring the birds is the Reconyx motion-sensitive camera. Placed outside nest boxes, these allow us to observe the type of fish parents are bringing for their chicks, such as their preferred cold-water Arctic Cod or the bulkier four-horned sculpin which is often rejected.

Island

The cameras can also record what is prowling around the colony while we are sleeping! I’ll note that this particular bear was not from my visit. Our bear encounters (three adults and a cub) all thankfully happened from a safe distance.

And where does all this data go? First it’s meticulously recorded into yellow Rite in the Rain field notebooks (George has hundreds now!), entered into spreadsheets, and becomes data points in the record and story of climate change.

3 Responses to “Tools For Research: Monitoring the Colony”

Lisa

This was such a fascinating read! Thanks for posting!

Maria

Thank you, Lisa!

Allan Gilhooley

Thanks for a sharing all this information, as well as the sketches. I found your blog when looking for help and ideas for sketching, not expecting the information about expeditions and climate research.