Science Vignettes: Forest Management

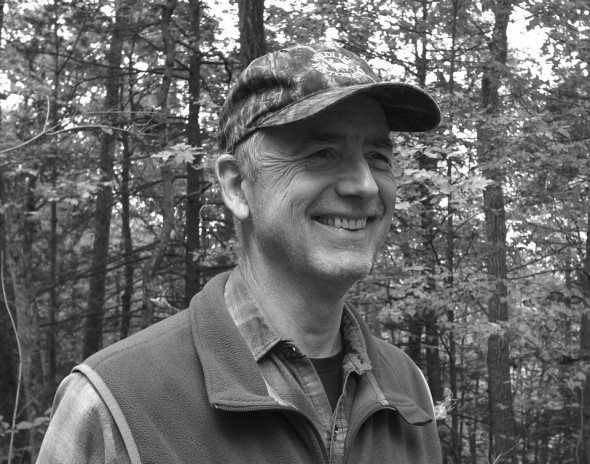

This is my second vignette from my October artist-in-residence with the Cary Institute of Ecosystems Studies in NY. (Read my first vignette.) Ray Winchcombe is a wildlife biologist whose research focuses on managing the whitetail deer program on the Institute grounds. When I met with Ray, it was bow hunt season and a hunter had just brought in the first deer.

I asked Ray how many deer lived on the nearly 2,000 acres of Cary Institute property. He explained that it’s hard to track specific deer numbers and that the better question to ask is whether the deer population is having a negative impact on the forested ecosystem.

Our goal through managed hunting is to keep deer numbers low enough so deer over-winter browsing remains low and allows the forest to propagate itself in a natural fashion. We need the next generation of seedlings to advance and be able to take over when older canopy trees start to die off. Each spring I examine seedlings to see what percentage of the major tree species are being browsed. Typically it’s less than 30%. If it gets up near 50% of available buds being browsed, then we need to remove more deer.

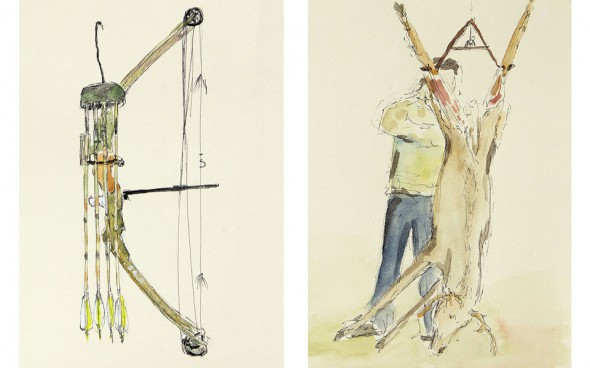

We have a managed bow hunt and shotgun season. Archery equipment is very effective, but it’s not as efficient as shotguns because you have to be very close to the animal. Bow hunting is a more intimate experience, though. It’s very discrete and I enjoy the opportunity to closely observe deer expressing their natural behaviors.

All hunters bring their deer back to our check station where we collect biological data. On antlered males, we’ll record the total number of points and antler beam diameters. We age the deer based on tooth wear, and also take dressed weights. We note who took the deer, the date, time, and grid number (where on the property it was shot). The bow hunters record how many deer they see and hours of hunting effort is kept for all hunters. All combined, these data give us an idea of the nutritional status of the herd and also helps us monitor changes in deer numbers.

Ray and I walked around the forest together and he pointed out the variety seedling heights, signs of a healthy forest. When deer over-browse, seedlings can’t grow to replace mature trees as they die off. This results in canopy openings that let in additional light, which can allow for invasive exotics to become established. Ray explained how profound the impacts can be.

You can actually get a species composition shift in your forest. As you lose trees producing fruits and nuts, you can lose mammals as well. Winds blowing through an open forest understory can dry up the damp forest floor, decreasing habitat for reptiles and amphibians. Birds are also heavily impacted by loss of vertical structure because many of them live and feed in mid-canopy layers. It’s a cascading effect.

This cascading effect reflects loss of biodiversity. We care about biodiversity for a variety of reasons, whether aesthetic, ethical, or moral. In my next Science Vignette, I’ll explore how it matters for our health.

Leave a Reply