Science Vignettes: Fog

During my October artist-in-residence with the Cary Institute of Ecosystems Studies in NY, I endeavored to meet the research community and create a series of vignettes based on excursions and conversations. The first scientist I met with was Dr. Kathie Weathers, an exuberant biogeochemist who specializes in studying the composition of clouds, particularly fog. We connected immediately over our shared affinity for atmospheric cloudscapes. Kathie invited me to hike at the Mohonk Preserve in the mid-Hudson Valley of New York state, one of her previous research sites. We explored the trails together and she shared stories of her work with me:

Being in fog, especially fog in a forest, is truly magical. It’s a different world in terms of color, in terms of sound, and importantly for the ecosystem, in terms of water and what’s in that water for ecosystems. Fogs are chock full of chemistry. I was surprised when we first started looking at the chemistry of fog just how concentrated it is. It’s packed with any chemical that can go up into the atmosphere and be incorporated into a droplet. That’s pollutants, that’s nutrients, it’s mercury, it could be pesticides, it’s nitrogen, it’s salt.

Biology of fog is my newest passion. Organisms, whether bacteria, fungi, or viruses, can be carried in fog droplets and move from one system to another. There are many more conections than we ever could have guessed between water, land, and air.

Kathie first started doing research in the Mohonk Preserve in the mid-1980s when she was studying clouds around the country. Her goal was to capture clouds and investigate their chemistry and how much water they bring to the landscape. I asked the obvious question, “How do you catch clouds?” Kathie explained:

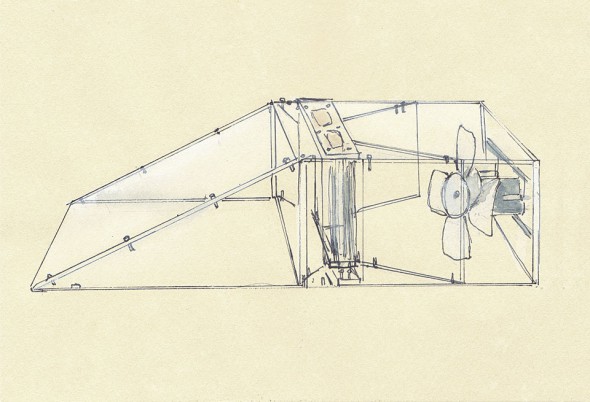

To catch clouds, it depends on whether you are interested in clouds up in the sky or clouds near the ground. Letting the trees capture the fog and then putting very simple funnels under the trees is one way we collect fog. Another method for catching clouds is to take a hollow cylinder and string fishing line up and down in the cylinder, so when the wind drives the droplets against the strands, they drip down into a funnel. You can also do that actively with a fan that pulls the droplets past a cartridge full of fishing line where the water impacts, drips down, and voila, you have cloud in a bottle!

Kathie also shared with me the “huge concern for those ecosystems around the world that are dependent on fog and how they will be affected the changes in fog frequency due shifts in climate.” In these specialized systems, life is oriented towards capturing fog. This may be how hairy or waxy a leaf is, or adaptations of beetles to catch droplets on their legs and stand upside down to drip water into their mouths.

Kathie’s research into what clouds contain and how they interact with the environment fascinates me. Ever since I remember, I have been captivated by the clouds; I even attributed my childhood misdemeanors to them. “Who scribbled on the wall?!” demanded my mother, “the clouds did it!” I remember replying. With her cloud catchers, Kathie is pinning down the ephemeral and unraveling their mysteries.

Leave a Reply