Artists in the Backcountry: Tony Foster

I’m delighted to announce the beginning of a new series, “Artists in the Backcountry,” which will feature the work of others with an affinity for art and adventure in remote regions. It’s great fun for me to meet and talk with these artists and I hope that you will enjoy learning about their work! If you have any suggestions for artists to feature, please let me know.

It’s my pleasure to introduce you to an artist I’ve long admired: Tony Foster from Cornwall, England. I first learned of Tony’s work in 2000 during his “World Views” retrospective at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle. His process of travel and field painting inspired me so much as I developed my own work as an Expeditionary Artist that I wrote him a letter to introduce myself. Since 1982 (the year I was born!) Tony has explored the world to create large watercolor diaries. You may learn more about Tony’s work on his website as well as in his beautiful new book, Painting at the Edge of the World that is well worth reading.

Where is home for you?

Home is Cornwall, England in a little village called Tywardreath. It’s on the south coast of Cornwall surrounded by sea and is, I think, the most beautiful county in England and a fabulous place to live. I live in a little perfectly straightforward village of about 1500 people. We have a pub and a butcher and a village shop and a church and a chapel and all the things we need. It’s really a marvelous place.

When did you become interested in art?

I’ve always been interested in art, ever since I was a kid. It was always the thing I was best at in school. When I was growing up it was never thought of as a way to make a living. I realized when I was 30 that I needed to take it more seriously and by the time I was 35, I was able to work on it full time. And now I’m 63.

What or who inspires you?

I’m pretty eclectic in the things I’m interested in. I’ve always enjoyed people like Richard Long and the economical way in which he sums up his extraordinary journeys. It was an inspiration for me to realize the idea of making work from experiences and from journeys and that art was a great way to express something about the world. Then there’s David Nash who also is very elegant in his means and in the way he puts shows together. Quite zen things almost… But then of course I cast back into history because I’ve always liked Thomas Moran and Frederic Church and all of those great adventurer artists. I was always bowled over by what they managed to achieve. I’m also a great fan of Damien Hirst. I’ve always liked the way he attacks subjects and he’s endlessly inventive.

I also love the way that Winslow Homer would sum up a landscape in just a few economical and absolutely authoritative brushstrokes and I did think at one time , “Why can’t I paint like Winslow Homer?” So I thought “Well if I go off with a 6ft x 3ft sheet of paper, I’m bound to start painting with bigger gestures and so on. I unrolled this sheet of paper in the field, sat down and two weeks later stood up again and stood back and I thought, “Bugger! It’s just more Foster!” It’s excatly the same as I always work, but just bigger. And so at that point I came to terms with the fact that that’s just the way I paint and there’s nothing I can do about it. It’s like your handwriting you know, it just comes naturally to you to do it that way and there’s no point in trying to alter it. Just be satisfied with what you do. And so I’ve stopped trying to be like Winslow Homer and I’ve decided I’m just going to be like me, only bigger. [laughs]

How do you balance studio time, business, and field work?

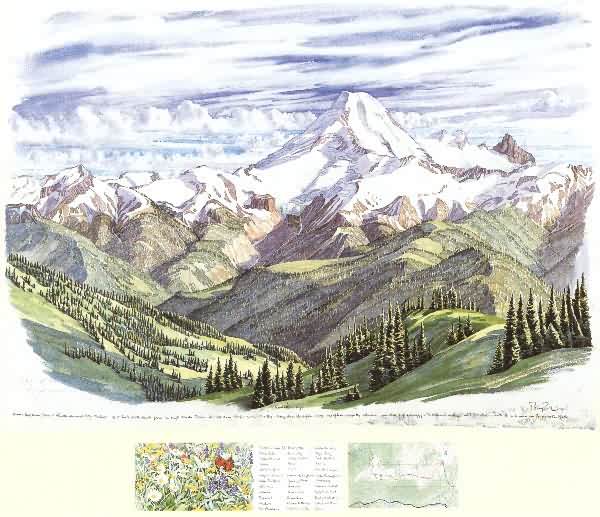

On average I’m traveling about four or five months a year in order to do the field work and then the rest of the year is studio time. You could say the balance of each painting works out to 5/12 field work and 7/12 studio work. The field work is undoubtably the most important and I don’t think these works could be created without it. I’ve never succeeded in making a painting from a photograph for example. Philosophically I have no objection to it, it just doesn’t seem to work and the paintings just don’t seem to have any freshness or quality about them. I’m simply trying to get a direct response to something and if it’s filtered through a camera lens, somehow it’s no longer direct enough for me. Which is why I spend the amount of time and effort that I do in order to stay in these places and paint. I think that when you’re painting on site, the problem really is not a lack of information, but an excess of information. You’re putting down as much information as you can gather in a limited time, because you don’t want to waste anything. When you get home to the studio you can look at it and think about how to make it work better as a painting. When my paintings come in from the field, they’re about 2/3 finished and have about them a lovely sort of freshness usually, but on the other hand they don’t necessarily work that well as paintings. And so the studio work is much more about making the background go back and the foreground come forward and your eye travel through the painting and all those other things that one has to do to make it succeed as an image.

What is your daily routine like?

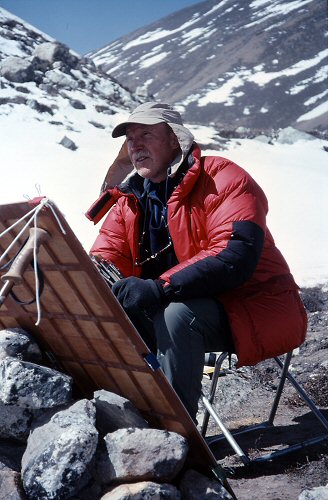

Daily routine in the field depends on where the hell you are. If you’re up Everest it’s a very different routine than if you’re down at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. But Everest, for example, the sherpas would bring us a cup of luke warm tea at dawn when the inside of your tent would be all covered in icicles from where your breath had frozen. As you sat up to accept the cup of tea they just were handing you, they unzip the tent for you and all the icicles fall down the back of your neck. So that wakes you up quite quickly. Breakfast was followed by sitting down to work. I would always mix gin with my paint water to keep it from freezing but it doesn’t work below -10 C, so sometimes I would have to wait for the temperature to rise. If I’m starting a new piece, I’ll probably have scoped out where I wanted to paint the day before and I’ll know exactly where I’m going to sit and I simply take my stuff out there, sit down to start drawing or lash my drawing board down and build an easel out of rocks and then lash the thing down to the rocks and tape the paper to it and start drawing. Or if I’ve already started a piece of work than I’ll simply return to where I was before and get on with it and work for two hours at a time followed by a tea break and then another two hours followed by lunch and then another two hours followed by a tea break and then another two hours. Usually I’d work till dusk so it might be a ten hour working day I suppose. I live in a tent (I worked out the other day that I’ve spent over five years in my tent) and usually I’ve got my pals with me so they’ll give me a shout when it’s getting dark and they’ve started cooking supper. Then I’ll roll up my stuff, head back to camp, have my supper, write my diary in my sleeping bag, and go to sleep. So it’s a pretty staight-forward thing really. Which is one of the delights of it in a way, that there’s nothing else to think about. You’re not answering the phone or writing emails, you’re just concentrating on what you’re supposed to be doing. And then when I’ve finished enough work on my painting, we’ll pack up and then move on to my next spot or until I find something else I want to paint. So that’s daily routine in the field.

In the studio, I get up about quarter past/half past seven, make tea, and go for a walk along the cliffs for an hour. Then I have breakfast in my studio about half past nine, work all day apart from lunch breaks and things until about seven at night. I always thought my life was fairly romantic in many ways, at least in other peoples’ eyes, but my niece came to stay with us and she came into my studio and said, “So Uncle, you sit in here, doing this painting for what 8, 10 hours a day?” And I said, “Yes, I suppose I do,” and she said, “God that must be so boring!” [laughs] So that’s basically it. Work, work, work.

What is your favorite tool?

My favorite tool is my #6 Kolinsky Sable paintbrush, apart from my Swiss Army knife which is one of my favorite things that I take in the field. And also my Jetboil stove which can make tea in about 5 minutes. That’s probably the thing that keeps me driving along the whole time is the chance that I’ll get to make tea every two hours. I also love my paintbox which is a wonder really to behold. It’s a little tiny Winsor Newton Bijou and it’s absolutely miniscule. When I walk into a big show of my work and look at all those things on the wall and think that every single particle of every single one of them has come out of this tiny, tiny paintbox, then it seems like magic to me. I never use any other box in the field or studio. When I give lectures, I have it in my pocket and talk about hiking. I say, “it’s important that you cut down as much as you can on everything.” Then I take it out and people just gasp. They can’t believe that I do all of these enormous paintings from this tiny box.

Do you have a favorite palette combination?

I suppose my colors are basically an earth palette because I’m painting the world. I use yellow ochre quite a bit and french ultramarine, and cobalt… Occasionally I break out. I’m doing some paintings of tropical sunsets at the moment and they are of course dazzlingly beautiful. I’m using all sorts of colors that I very seldom use like Winsor Yellow and rose madder or permanent rose.

Do you keep a journal or a sketchbook?

You know, I don’t. I’m very rigorous about writing my journal when I’m in the field becuse it forms an important part of the work. but when I’m home, no, I never do. And I very seldom do sketches. I either do small paintings or I do big paintings. I don’t do sketches for the big paintings- I simply sit down, unroll a 6ft sheet of paper, unfold a 6 ft drawing board and sit down and get on with it. I suppose I’ve built up in confidence in order to get to that kind of stage where I feel capable of doing that on Everest for example. I think it’s the big things that have established whatever reputation I’ve got. Because I think a show of small things people would look at and think “oh, well that’s nice. Next time I go on holiday I think I’ll take a sketchbook with me.” But when they see the big things they think, “holy shit, how the hell did you do that onsite?” It puts it into a different category somehow I think. People don’t expect watercolors to be powerful. Watercolor doesn’t have to be on a domestic scale.

What’s your next big adventure?

I’m going to be comparing the Rio Grande and the Amazon. Politically they’re both really hot issues. The Rio Grande is being used and abused- it’s being drained, it’s being polluted it’s being spoiled in many, many ways. And yet there’s places along the Rio Grande which are just exquisitely beautiful. Similarly in the Amazon, there so many places that are just completely untouched. Intense, intense beauty. And yet of course there are massive amounts of logging, gold mining, all sorts of stuff going on which is destroying it. So I think it’s time I did a show about that.

Thank you, Tony Foster, for taking the time to share your work! And best wishes for your future adventures.

6 Responses to “Artists in the Backcountry: Tony Foster”

Anna McKee

Thanks for the info on Tony Foster, you must be very excited to work with him this summer! I will definitely check out his book.

Joi

nice, very nice article and great idea Thanks Joi Electa

Lisa

Thanks so much for posting! Great read! I’ve been a fan of Tony’s for years and I’ve watched some videos from The Foster and I could hear his voice as I was reading. I laughed out loud over “Bugger! It’s just more Foster!”

Maria

I’m so glad you enjoyed it, Lisa! I’m such a fan of Tony, he’s an utter delight to talk with and incredibly inspiring as an artist.

Carmen

This was fascinating! What beautiful work and a great lesson on the power of a small palette and limited colors.

Maria

So glad you enjoyed it! Tony is a real inspiration.